1. University-Community Engaged Research and Development with Information Communication Technologies for development (ICT4D) and bridging the digital divide

Driven by UNIMAS vision and its mission to generate, disseminate and apply knowledge strategically and innovatively to enhance the quality of the nation’s culture and prosperity of its people, researchers put ‘knowledge to action’ through community-engaged research and development. This was carried out through multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach at one level, and at another level, adopting Participatory Action Research and bottom-up methodologies. This is to ensure multilevel collaboration on R&D programmes with information communication technologies for socioeconomic development in rural areas and amongst remote communities. As a result, programmes are designed, planned and implemented with close consultation between researchers and members of the community. Outcomes of the research were presented to the community members at the village halls, and their responses are considered into the final report and in the design of the initiative.

2. Local needs and socio-cultural contexts

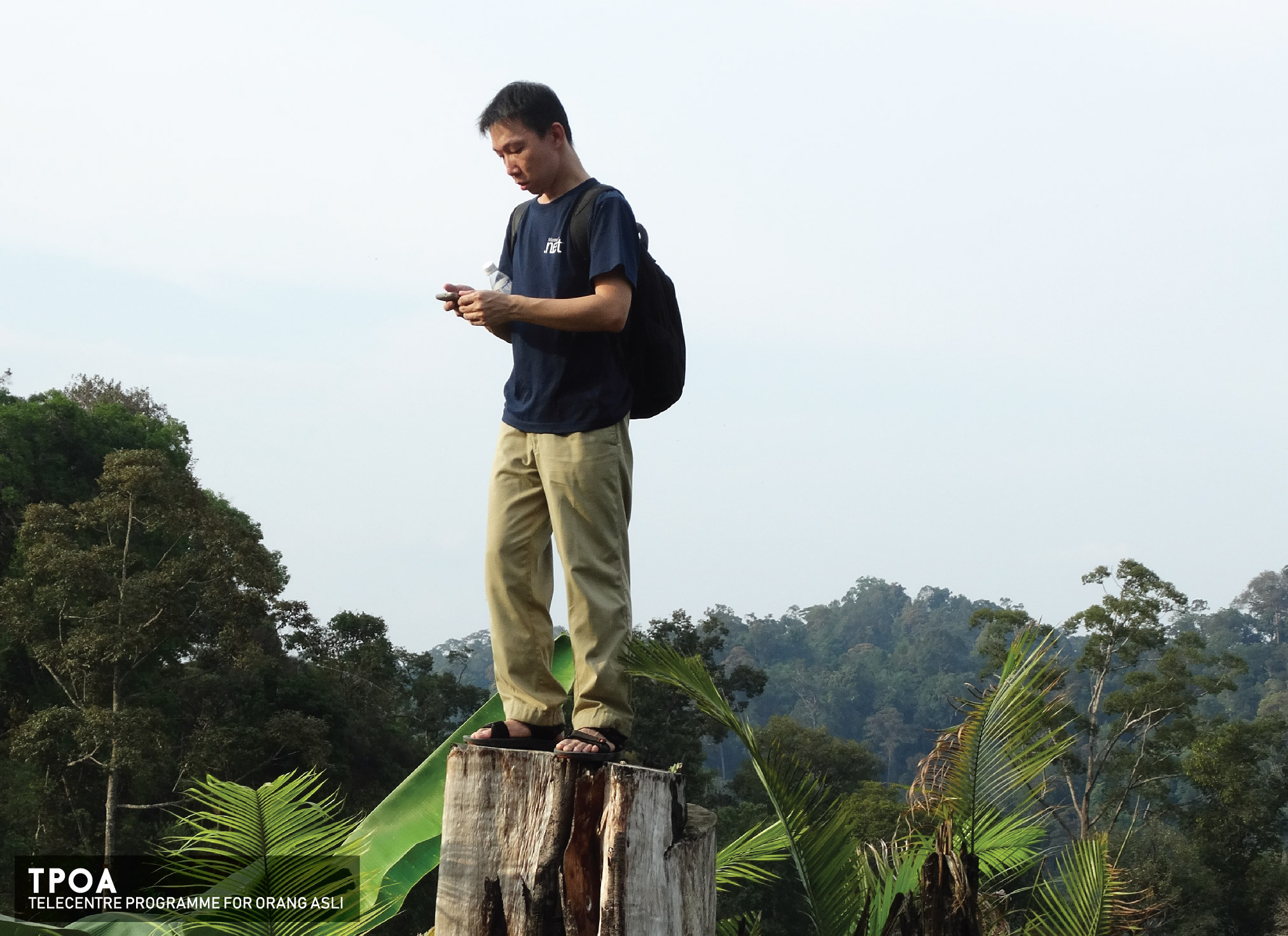

Since 1990s Needs Analysis became an important tool promoted by International Labour Organisation to ensure that development benefits will reach the poor in society. In this case, it is adopted to ensure that the Orang Asli communities at the four remote sites gain socioeconomic benefits from the introduction of the new information and communication technologies in their environment. The main activity of the initiative is to conduct preliminary assessment of actual ICT needs and uses in the communities to be served by a telecentre. Some of their needs are much more specific to the geographic area. In addition, people’s behaviors, customs, and motivations for usage, including perceptions and attitudes toward technology are all strongly influenced by their social and cultural context.Therefore the cultural characteristics of each community (especially since these are traditional communities) have been key issues to consider when these new and emerging technologies were introduced and implemented within their geographic area and the ecology surrounding them. These are important in order to examine what role emerging technologies might play and what effects they might have in different cultures. That is, technologies can be developed/designed so as to enrich and fulfill people’s lives where by services and interactions provided by science and technology truly match users’ social requirements, expectations and cultural contexts.

3. Responsible Research and Innovation amongst rural communities

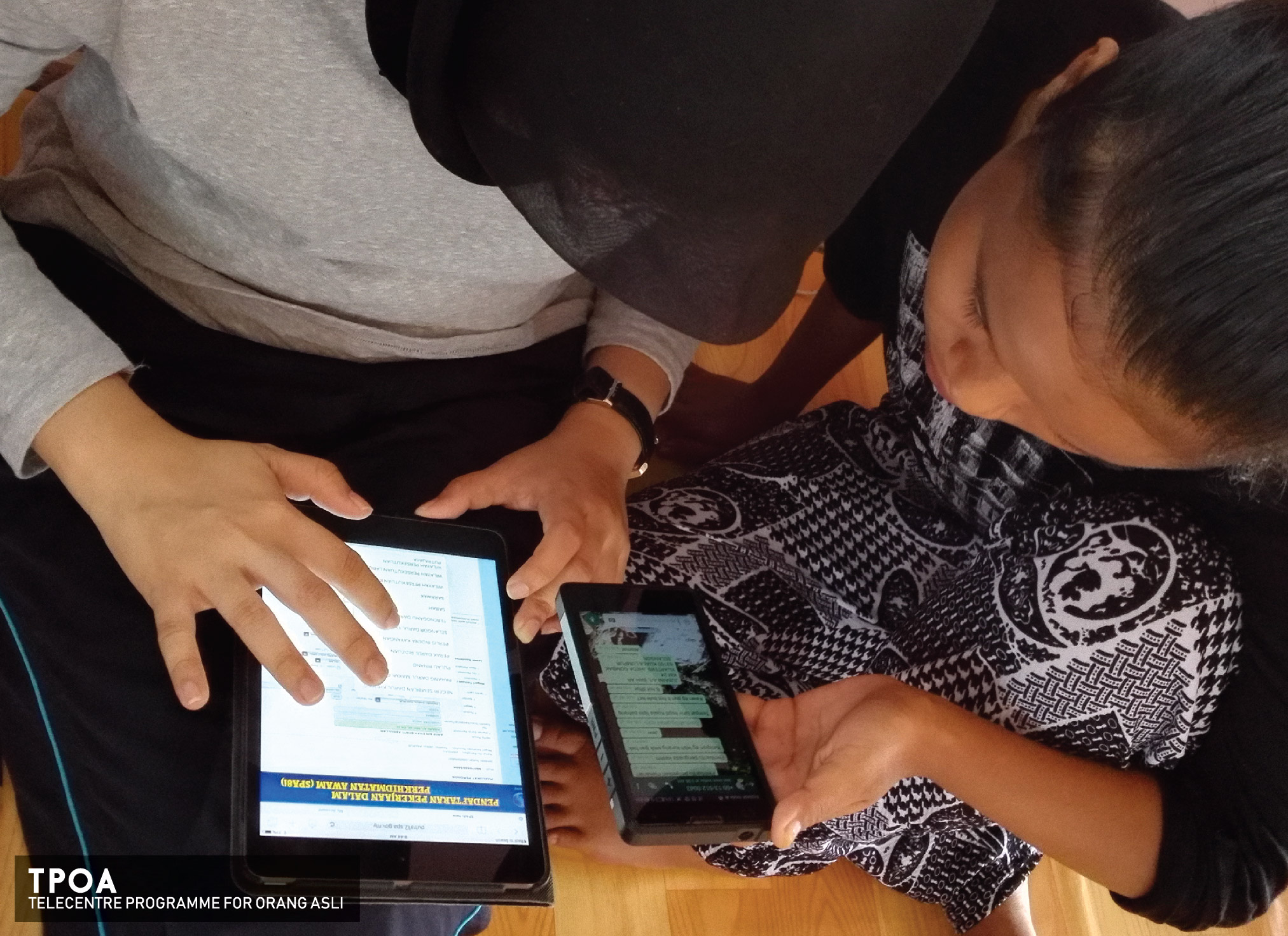

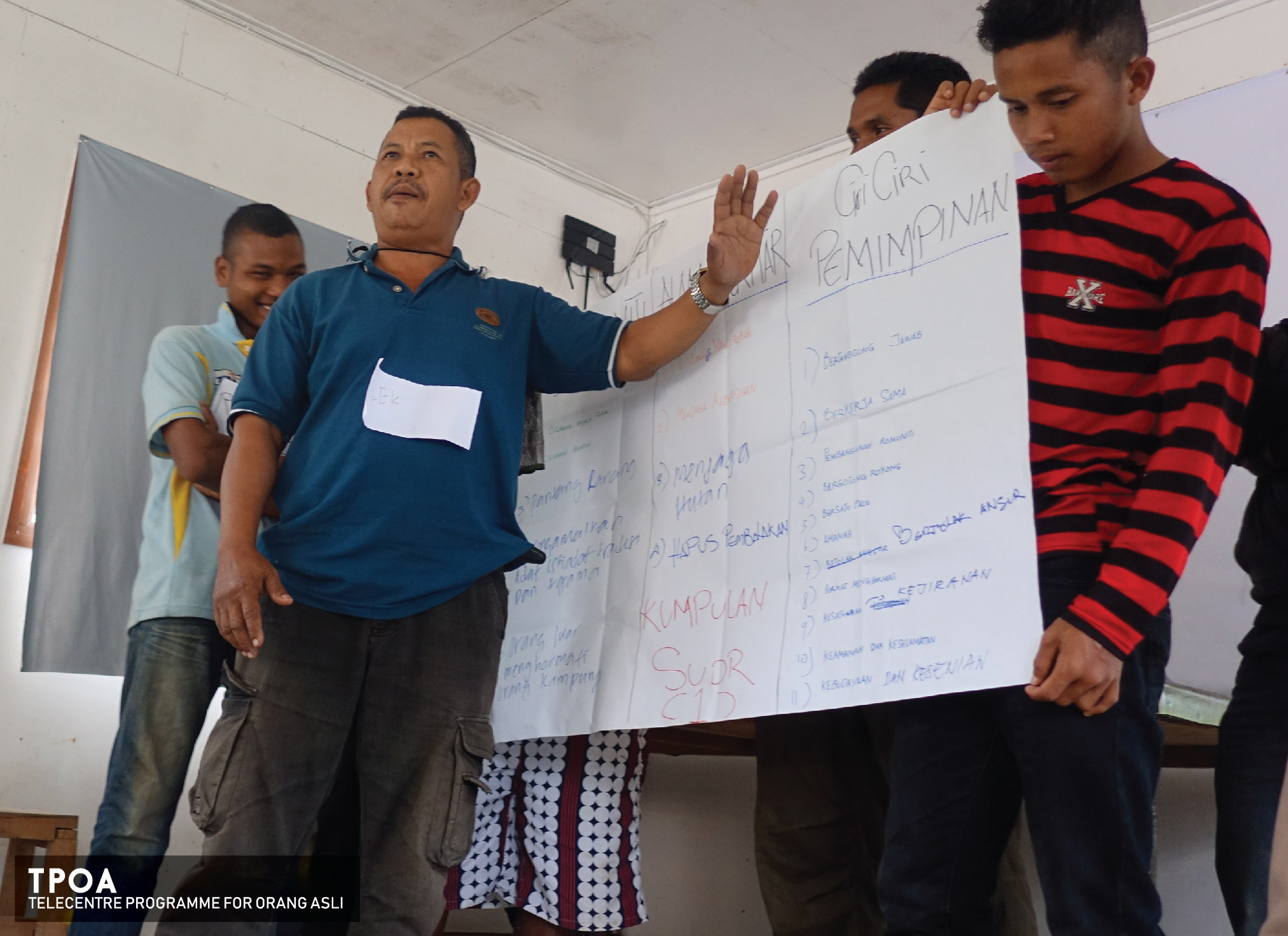

To ensure deeper and meaningful engagement of research and innovation, design and planning process and implementation have to be contextualised. This in order to ensure long term ethical and societal impacts. The activities and outcomes are shaped by the aspirations, dreams, expectations and needs of the local communities. In this case communities are not simply “adopters or consumers” of gadgets and technologies but more importantly they are knowledge creators in their own right. In other words, the R and D programmes design, planning and implementation as much as possible were submitted to local governance structure and decision making mechanisms, and the technologies are adapted to local needs and socio-cultural contexts. The community telecentres at the four sites became living labs for social innovation. In the process and through joint activities, reseachers and members of communities directly participated in co-creating knowledge.

4. Ethnodevelopment

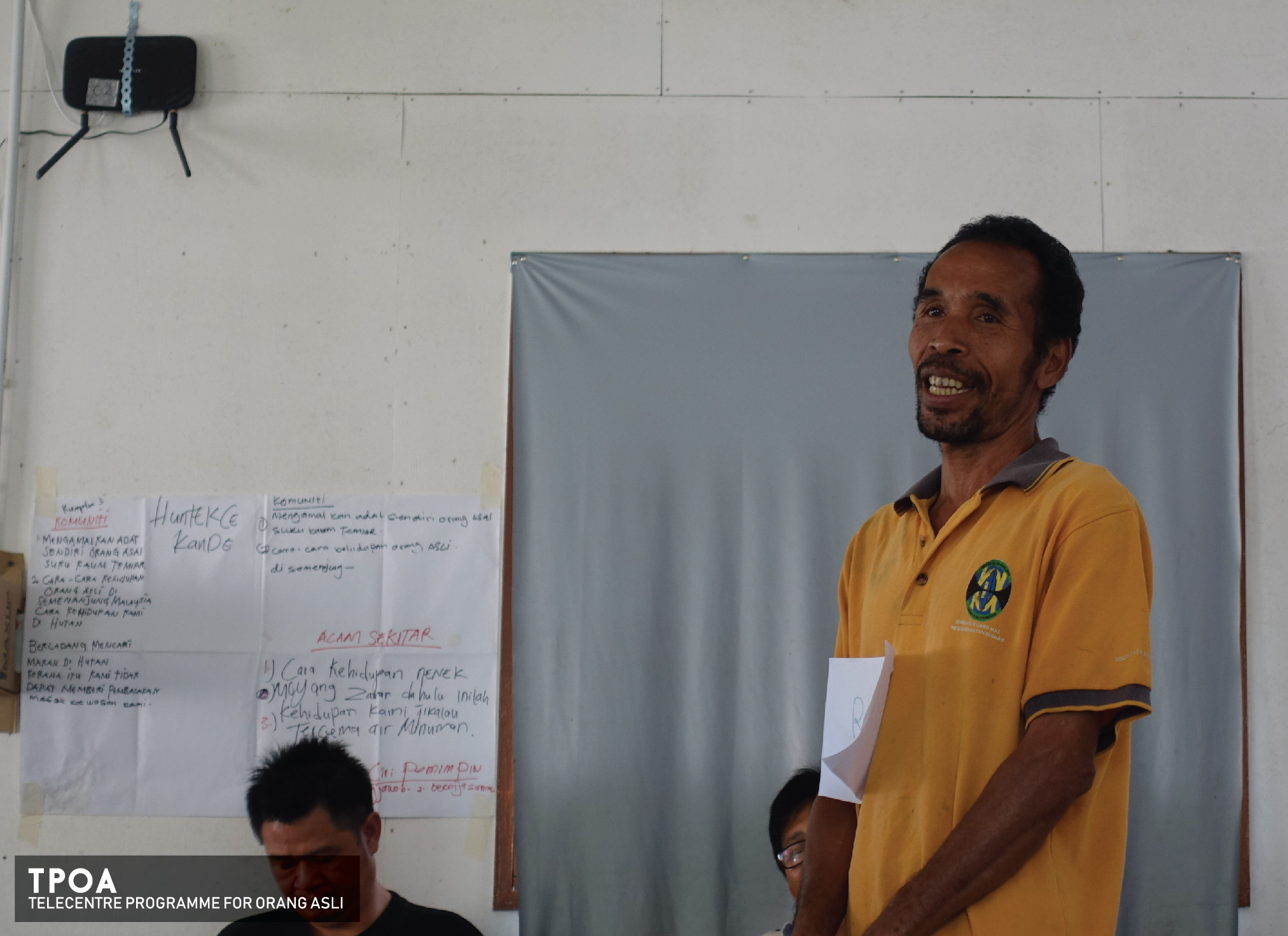

Ethnicity, according to Hettne (in Willis, 2005: 122), “ has been a neglected dimension in development theory” and practice. Therefore there has been argument that ‘development’ approach at national scale needs to focus on the population’s ethnic diversity. This has led to the emergence of ethnodevelopment approach, which focuses on the problems of ethnicity and development. In fact, the World Bank perceives ethnicity as a form of ‘social capital’ particularly the ways in which ethnic identities are used to mobilize themselves within their own territory and available community’s economic resources. In this case, the approach is based on the fact that Orang Asli communities have knowledge, resources, and are more aware of their local challenges, and if organized they can be the impetus for their own empowerment.

5. Participative Development and Human Development Approach

Participative development move the gauge of development programmes from mega structures such as the roles of the markets and government policies towards the people as the beneficiaries.

Amartya Sen (1998) an economist and ethicist, proposes an approach to economics and processes of development that focuses on human agency and social opportunities rather than on mega-structures such as markets or governments. By placing people as main actors at centre-stage, the process of development can empower them to participate in the decisions that shape their lives. Local residents and communities become agents of development and change, rather than recipients or victims of development.

Through representative local participation, we identified development challenges, prioritized them and later drew a community action plan to be implemented by a Community Based organization that we created during the process. In this case, the local Orang Asli communities were engaged at all levels of the project: design, planning and implementation. By placing people at centre stage, the process of development empower them to participate in decision that shape their lives. This is the main purpose for the formation of the Community Advisory Board. Their main role is as gatekeepers. They are to protect community interests – stopping exploitation and ensuring community benefit. This is also to provide meaningful and substantive input into the research process from its inception to conclusion that are made around the project for the benefit of the community.

6. Sustainable Development for sustainable participation

Since UN Conference in Rio Jeneiro in 1992, ‘sustainable development’ has become a key element in development theorizing and policymaking. The key argument is that for development to be powerful and long-lasting, it must allows communities to continue to grow through ownership and responsibility. It is an empowering process in that it places those being affected at the centre of their own development. This is by equipping communities with necessary knowledge, skills and appropriate values and attitudes to act and manage their own development.

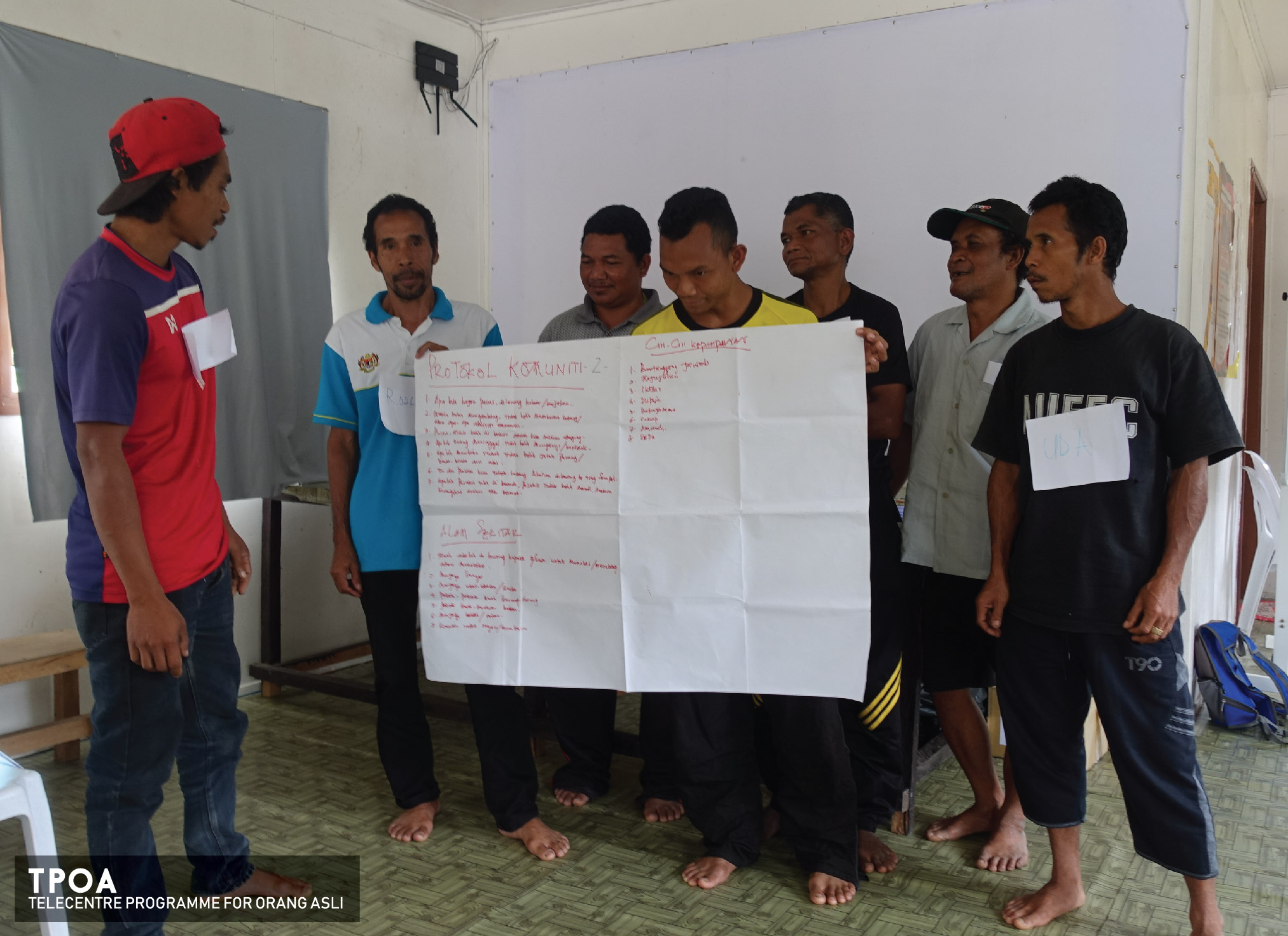

7. Community Protocol in University- Community Engagement

Nowadays universities are required to advance knowledge beyond the confine of traditional knowledge areas known as “disciplines” to engage with industries and also local communities. This requires an understanding of existing customary protocols and governance systems in the communities. To address this concern, local communities at the four sites have begun to document and develop their protocols into forms that can also be understood by others. This to ensure that researchers respect their customary laws, values, and decision-making processes, particularly those concerning stewardship of their territories and areas. Henceforth, all R and D activities are to be carried out in a culturally-appropriate manner, and that the communities understand the implications of the engagement. Respecting and acting according to community protocols help to ensure that any intervention will not lead to conflict and deterioration of social cohesion and bring negative impacts on the environment.

8. Responsible Research and Innovation amongst rural communities

To ensure deeper and meaningful engagement of research and innovation, design and planning process and implementation have to be contextualised. This in order to ensure long term ethical and societal impacts. The activities and outcomes are shaped by the aspirations, dreams, expectations and needs of the local communities. In this case communities are not simply “adopters or consumers” of gadgets and technologies but more importantly they are knowledge creators in their own right. In other words, the R and D programmes design, planning and implementation as much as possible were submitted to local governance structure and decision making mechanisms, and the technologies are adapted to local needs and socio-cultural contexts. The community telecentres at the four sites became living labs for social innovation. In the process and through joint activities, reseachers and members of communities directly participated in co-creating knowledge.

9. Building a TPOA Learning communities

Breaking away from the conventional notion that universities create, diseminate “knowledge,” TPOA activities built a learning community which constitue researchers, the four communities, and other communities in Sarawak and Sabah, policy makers and development practicinioers. It is a shift of emphasis with focus on indivual to learning as part of a community. Aptly highligted through the biennial eBorneo Conference, which allows for community to community training and learning, development practicioners and policy makers learning from each other through participative listening and discussions. This is an important process in redefining knowledge and co-creating new knowledge (understanding, perceptions and practices). Led to the emergence of community scholars who are expert in their local histories, surrounding working side by side with university scholars to co-create and co-produce culturally appropriate learning and teaching practices. Building a learning community that is defined by a common purpose.

As a learning community, the eBario Knowledge Fair (eBKF) features open discussions, workshops and walk-shops (in which participants are taken on a walk around the village to illustrate the topic they are discussing) rather than single speakers giving talks. As an unconference it is organized, structured and led by the people attending it. Instead of passive listening, all attendees and organizers are encouraged to become participants, with discussion leaders providing moderation and structure for attendees. The event showcases the achievements that participating researchers working with communities have made with ICTs and it elicits local knowledge and information from community members that can be used to devise further ICT innovations and implementations towards sustainable development. The event format helps attendees draw strength and inspiration from each other during the discussions and exchanges, which are free-flowing, open, flexible, and non-hierarchical. Compared to traditional dissemination mechanisms such as seminars, conferences and other forums, knowledge fairs have been demonstrated to be innovative, dynamic and effective scenarios for identifying and promoting experiences and for facilitating the transfer and re-utilization of the knowledge derived from the variety of encounters that take place.

10. Physical Telecentre Sustainability

To ensure physical sustainability, telecentres were built using local products and materials, and with local material, local skills and capabilties and local design. Local practice of gotong royong was also employed to maintain social cohesion and to inculcate sense of ownership.